Despite being a real thing many other places around the world, high-speed rail is at risk of becoming a meme technology in the United States. Leading the case for pessimism is the endlessly depressing saga of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, which will end up spending $35 billion to finish a line that will not connect San Francisco to Los Angeles. On the other side of the country, in Florida, Brightline—the private sector’s first attempt at quasi-HSR—is saddled with debt and running in the red. After a few jubilant years under the Biden administration, Amtrak is now in Trump’s crosshairs, its nascent ambition to build the formerly-private Texas Central project between Dallas and Houston snuffed out by new Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy.

The failure of the public and private sectors to deliver true high-speed rail leaves little room for optimism. Most of the eggs of the high-speed rail movement are now in the basket of Brightline West, the high-speed rail line greenlighted between Los Angeles and Las Vegas; time will tell if it is able to overcome the political turbulence and cost disease that has killed peer projects. As we approach the 2030s with no high-speed service beyond Acela and Brightline—and none exceeding 150 miles per hour—it’s worth revisiting the value of pursuing HSR in this country at all.

The fundamental challenges of passenger rail

The burden of the fixed route

Modeled simply, there are three physical components of any transportation service: the termini, the route, and the vehicles. For example, for automobile travel, the termini are parking lots, the route is the roadway network, and the vehicles are the cars, buses, and trucks.

Each of these components contributes a bucket of costs when creating a new transportation service. Air and marine travel benefit from the route being provided by nature1—the bulk of the investment will be in the termini (ports) and vehicles (planes and ships).

In contrast, automobiles require continuous surface infrastructure to travel between any two points. To drive a car from city A to city B, you need to pave the entire way between the two points and have parking at each end. Roads are relatively “dumb” infrastructure–there’s not much to building a functional road beyond laying down some reasonably smooth asphalt, painting some lines, building some overpasses and ramps, and installing some traffic lights and signs. All of this is highly standardized and none of it is especially technical. Once in place, roads do not require much active management—they need to be maintained, yes, but there is no one sitting in a control tower directing the movement of each and every vehicle.

Contrast these modes of transportation with rail, which requires:

- Termini in the form of stations, which grow considerably more complex with scale (see the trackwork leading up to any major urban station)

- Point-to-point route infrastructure which must be built to a high level of precision (continuous steel rails with mild grades and minimal distortion) and actively managed once operating (e.g., through dispatching and/or control systems like PTC)

- Large vehicles that, like planes and ships, require professional operators

Rail is inherently more complex. It combines the disadvantages of motorized transport (continuous point-to-point infrastructure) with those of air and marine transport (large, capex- and opex-intensive vehicles).

We should expect the incremental investment required to create a rail connection between any two places to be higher than a road, air, or water connection—and, in practice, that’s what we see. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t build rail anywhere, but we should acknowledge that the cost of doing so limits the number of places where the return on investment is likely to be positive.

The dual role of the state

Another challenge to building high-speed rail is that the proprietor (i.e., the state) must build the infrastructure and operate the vehicles.

This is not true of road transport, where the state builds the infrastructure (roads and highways) but private citizens and businesses purchase, maintain, and operate the vehicles.2 It is not true of air or marine travel, where the state builds ports and the route is provided by nature. The fact that, for any greenfield rail project, the state must build hundreds of miles of track, procure several dozen (often custom) locomotives and railcars, and then operate a passenger transportation business in perpetuity—all while maintaining the assets—introduces an incredible amount of complexity and cost. The scope of what is required to create a new high-speed rail line is well beyond the typical state-funded transportation project.

This is not an insurmountable challenge—in many countries, the state both builds and operates high-speed passenger rail—but it is awkwardly out of step with the history of rail development in the United States. Most rail trackage in the U.S. is owned by the private Class I freight railroads, and neither the federal government nor the states have ever played a major role as rail infrastructure managers (Conrail notwithstanding). Rail in the U.S. has been privately owned and operated since the very beginning.

After the railroads ditched their passenger businesses and aggressively consolidated in the last century, much of the institutional knowledge on how to build and provide good passenger rail service evaporated. Yes, Amtrak picked up the scraps, but running a handful of lines on tracks mostly owned by others is a far cry from the elaborate passenger networks of other countries. Meanwhile, most European countries nationalized their rail infrastructure in the early 20th century and never abandoned their passenger networks.

What California and others are now finding is that it’s very difficult to recreate passenger rail from scratch. There is no culture of or public familiarity with rail travel to provide political support for consistent, uninterrupted investment. There is no infrastructure to incrementally improve upon—outside the Northeast Corridor, the best routes for passenger service are either owned by the Class Is or have been abandoned. There is no industrial base of engineers, contractors, and manufacturers who know how to build rail and locomotives cost-efficiently, and there is no “standard” for American rail construction that is optimized for the supply chain and regulatory requirements of this country.

In building high-speed rail, we are asking American states to do something they have never done. On some level, we should expect failure and massive cost overruns. The path to creating a high-speed rail industry in this country will be paved with suffering and debt.

Roads and highways offer a useful contrast. America knows how to build good roads cheaply. Highways have always been under the purview of the government—every state has well over a century of experience building them. Investment in roads has been healthy and consistent, supported by trust funds that span changing political winds. There is a sophisticated industry of engineers, contractors, and suppliers engaged in continuous road-building under well-established federal and state guidelines that ensure a high degree of standardization. And, as mentioned before, there is no expectation that the state provide the vehicles to be driven on the roads—so a large source of complexity is entirely absent.

So why build high-speed rail?

The advantage of passenger rail is that it can move a very large number of people in a small terrestrial footprint. Rail has distinct advantages over each of the other primary modes of transport:

- Versus roads: Rail has a higher throughput (people moved per hour) and takes up less space, both along the route (compare the width of a highway to that of a rail line) and at the destinations on either end (compare the cumulative amount of parking in cities to the size of a train station serving an equivalent number of people).

- Versus air: Rail has higher throughput, consumes less land, and is able to access city centers. It is also generally less vulnerable to severe weather.

- Versus water: Rail has a higher throughput and is able to access areas away from the ocean or a navigable river, lake, or canal.

Therefore, the case for building high-speed rail is strongest for pairs of cities with the following characteristics:

| Characteristic | Example |

|---|---|

| There is strong travel demand, and demand is expected to remain strong for the lifetime of the investment (several decades) | Los Angeles and San Francisco are very large cities that will remain very large for the foreseeable future, and the air route between them is the fourth busiest domestic route in the U.S. |

| Existing modes of transport are heavily constrained, or their capacity could be used more efficiently | The major airports in the Northeast—e.g., DCA, LGA, EWR—operate at capacity and cannot be expanded; shifting regional flights to rail could create room for more long-distance flights better served by air travel. |

| High-speed rail can offer a competitive travel time versus driving or flying (i.e., the cities are not too far apart) | Dallas and Houston are ~250 miles apart; high-speed rail could cover the distance between city centers in ~90 minutes versus 4 hours driving or ~60 minutes by air. |

| The terrain is not too challenging—there is a feasible overland route between the cities | The route between Miami and Orlando is flat, and there are existing Interstate highway alignments that can be used for rail. |

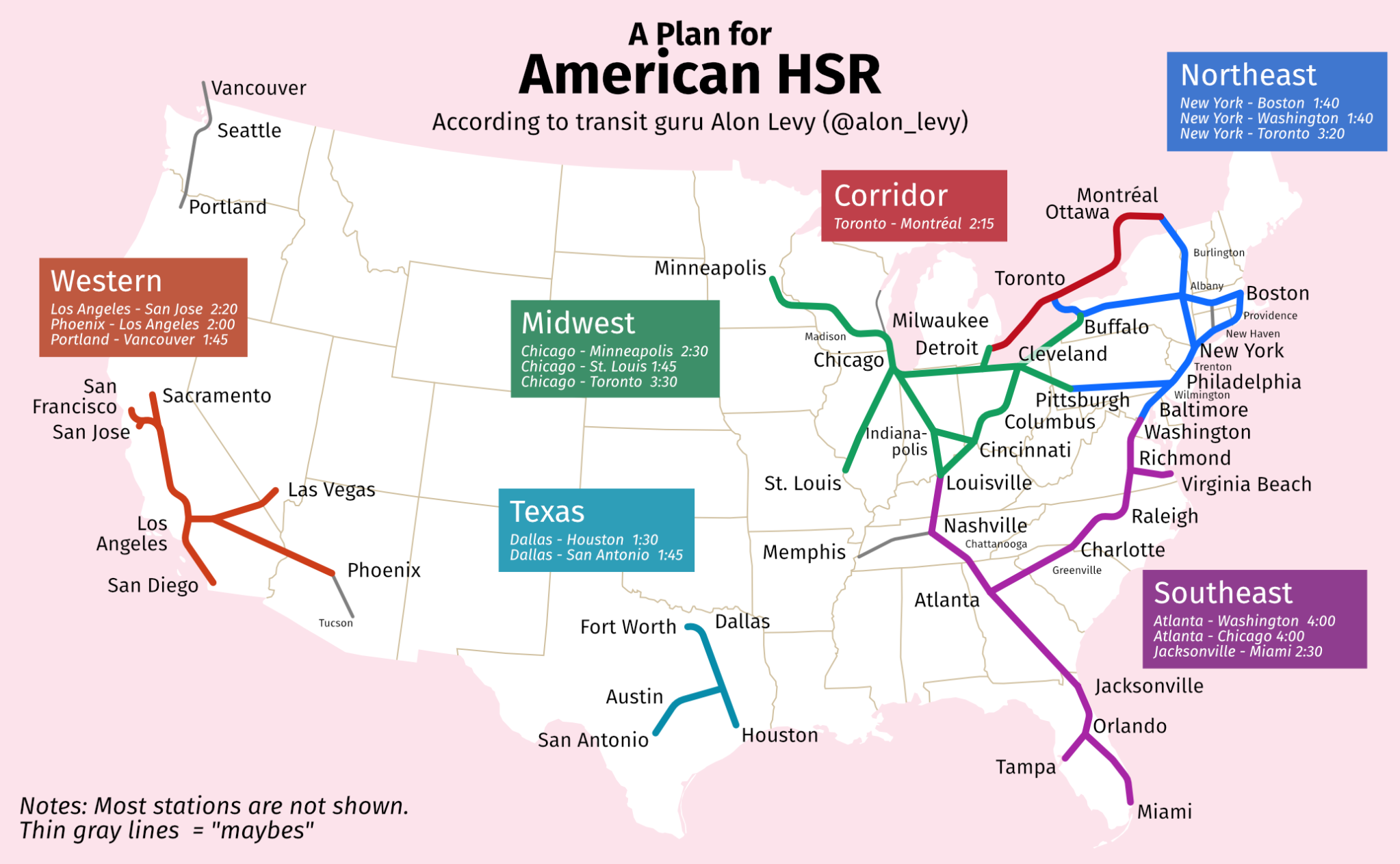

There are several city pairs in the United States that meet these criteria. The analysis has already been done—I think Alon Levy’s map (below) is basically correct.

Is it worth continuing?

Los Angeles–San Francisco is a good route for high-speed rail. The problem is not the idea, it’s the execution. California has shown it does not have the state capacity necessary to build the line.

This is disappointing, because California does have the capacity to build other great things. The gradual expansion of the LA Metro, while overpriced, is impressive—the city and state are putting in exactly the sort of sustained investment that’s needed to build a comprehensive transit system. California would not be able to support a population of 40 million without great infrastructure. Sadly, high-speed rail is beyond what California can handle precisely because it is a type of infrastructure that the state has no experience building, which allowed the effort to be consumed by cost disease and administrative incompetence.

If the nation’s largest and richest state can’t build an obvious high-speed rail line between its two largest cities, is there any hope for HSR elsewhere in the country? I think it can be done, but it’ll require a very different approach than was taken in California. If political momentum ever exists again to build HSR after California’s failure, the next project should…

- …avoid “everything bagel” impulses that expand the project’s scope beyond the provision of a high-speed rail line. Rail projects should not be about creating jobs, advancing “equity”, or building things that are not a rail line.

- …relatedly, accept simplicity in version 1.0. California HSR is hamstrung by its grandiose design, which includes massive viaducts and huge rural stations.

- …be located somewhere flatter. A major reason I don’t think California HSR will ever be completed is because none of the current construction addresses the gorilla in the room, the 28 miles of tunnels required to connect the Central Valley segment to San Jose to the north and Burbank to the south. (The California HSR Authority estimates the cost of the Palmdale-to-Burbank tunnels alone at $28 to $45 billion. We should ask—how did Switzerland build the world’s longest and deepest rail tunnel, 7 miles longer than the combined length of the California tunnels, for only $12 billion?)

- …partner with a private entity with experience building and operating high-speed rail and actually heed their advice. French rail company SNCF somewhat famously backed out of a joint venture to build California HSR after the state government refused to adopt its recommendation to build a simpler route along Interstate 5.

The Texas Central project to connect Dallas and Houston ticked a lot of these boxes, but unfortunately the state of Texas and the Trump Administration could not see its merits. Brightline West also seems more viable—though seemingly already behind schedule—and I hope it’ll end up serving as the first example of true high-speed rail in the U.S.

Our federal system dictates that any future high-speed rail project will need to be championed and executed by individual states, just as the Interstate Highway System was. I think high-speed rail is most likely to succeed in a builder-friendly, fast-growing, purple-ish state that isn’t beholden to red tape or leftist special interests. Texas and Florida are ideal candidates, and the fact that Florida got a privately-owned passenger rail line before any blue state is a testament to how red-leaning places are actually willing to build.

What about the counterfactual?

I’ve discussed several reasons why high-speed rail can be beneficial—but this is not enough to say we need it. To do that, we need to consider what happens if we don’t build it.

The plain truth is that the United States has spent the past half century not building high-speed rail outside the Northeast Corridor and things have been okay. The cost of the absence of high-speed rail to the average American is not immediately obvious.

The first-order effect of not having high-speed rail is that we must fly or drive to travel between cities. As a result, there’s a lower overall supply of transportation capacity between cities, and we must reserve some airport and highway capacity to accommodate short-haul travel. For the average American, this means they may pay more to travel between cities than they would in a world where a high-speed rail option existed, and they may experience more congestion on highways and in airports.

This impact is larger for time-sensitive travelers who are looking to get between cities quickly. There is plenty of highway capacity between our cities; if you’re not time-constrained, the absence of high-speed rail is largely inconsequential. But many of us—especially those of us traveling for business—do value our time, and the lack of flexibility in air travel becomes glaring.

This is especially obvious if you live in a non-hub city like St. Louis, where there are not many direct flights. To get from St. Louis to other Midwestern cities without driving, you almost always need to connect through Chicago O’Hare, turning what would be a 60-to-90-minute direct flight into a 3-to-5-hour affair. This is typically faster than driving, but it’s far slower than the hypothetical high-speed rail alternative. Residents of non-hub cities also have fewer flights to choose f due to constraints on air route capacity caused by a lack of planes or airport capacity. And both hub and non-hub residents must deal with last-mile transit to and from airports, which are not typically located near a metropolitan area’s center of population or jobs.

How many people are really affected by this? ~200 million people outside the 26 metropolitan areas that contain a hub for one of the 7 mainline passenger airlines.3 Assuming about half of those people fly at least once per year, and 40% of those people are traveling intraregionally (e.g., a distance where high-speed rail would be competitive) then ~40 million people are paying more—in time and/or money—for intercity travel due to the absence of high-speed rail. This is a very unsophisticated estimate, but the point is that a large number of people in this country are not well-served by the air transportation network.

There are also broader economic effects on metropolitan areas that are interesting to consider. Air network connectivity is an important ingredient for economic growth; it is not a coincidence that many of the most economically successful and resilient cities are also a hub for at least one major airline. St. Louis losing its hub status following the TWA–American Airlines merger in the early 2000s likely impacted the city’s economic prospects. The costs imposed by limited high-speed transportation capacity to and from our nation’s second- and third-tier metropolitan areas likely fuels the ongoing aggregation of economic activity into coastal metropolises. Perhaps high-speed rail has a role to play in “democratizing” our economy and extending prosperity into struggling and overlooked regions. As long as airlines retain a hub-and-spoke network model and airport capacity is constrained, there is little hope that places like Fort Wayne, Indiana, Springfield, Illinois, and Louisville, Kentucky will ever get frequent high-speed transportation service without high-speed rail.

Perhaps driving between cities is sufficient and it’s not worth risking another California-style boondoggle to bring high-speed rail abundance to non-hub cities. But even with the advent of self-driving cars, maximum intercity driving speeds will likely remain capped at 60 to 80 miles per hour due to highway geometry. Both the value of our time and demand for intraregional transportation will rise with wages, increasing the burden that a lack of high-speed options places on residents of non-hub places. It will become increasingly difficult for these places to compete in an economy that values connectivity.

While high-speed rail must compete with driving and flying for passengers, perhaps it’s best considered as a tool to increase the overall availability of high-speed transportation—both the capacity of high-speed travel between major cities and the number of cities served. Air travel is an incredible and revolutionary innovation, but it has its own set of constraints and drawbacks that cannot be easily resolved. If it persists as the only form of high-speed travel in the U.S., we will have to live with the costs—which will fall disproportionately on residents of smaller cities.

Achieving “abundance” in our society and economy requires thinking beyond the constraints imposed by our current infrastructure. We should consider the role of all technologies at our disposal, from self-driving cars to high-speed rail. America does not need high-speed rail, but the freedom of movement it could unlock for millions of Americans is worth giving it a try. It can be done—just perhaps not in California.

- Ignoring, for the sake of argument, investment in dredging and expanding waterways.

- Bus systems are an exception, but they are considerably less complex than rail and common across the country.

- Alaska, American, Delta, JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit, and United. I excluded Allegiant, Frontier, Hawaiian, and Sun Country.